We need to talk about GenAI

TL;DR:

Generative AI (GenAI) is frequently presented as bringing benefits for individuals, industries and even all of humanity¹. However, the ownership, production and execution of GenAI raises a series of ethical questions for its use.

Discussion is needed about whether and how GenAI can be incorporated ethically and responsibly into arts and health practices.

Drawing upon evidence regarding GenAI’s impacts, this article presents 5 ethical tensions for GenAI’s use in the arts and health practices, and suggested actions.

Like Bernstein (1), I don’t actually care too much about AI itself. I’m not anti-AI. I see it as part of a long history of technologies created by humans, albeit a potent one. AI presents some exciting possibilities and claims about these are pretty easy to find. It also brings alarming harm and risks².

So, like Mark McGuiness (2), it’s not that I necessarily want to talk about AI but I think we need to.

More specifically, I think we need to talk about the context of AI and in particular, generative AI (GenAI). This is because GenAI’s ownership, production and execution entail a series of ethical issues that seem to be at odds with some of the goals and values of both arts and health sectors in which I practice, which at their core advocate for social justice, inclusion and progressive social change ³, ⁴.

(As a certified coach, I also believe the coaching industry needs to engage with these core ethical tensions⁵ but that is for another note).

I do not provide an in-depth analysis of GenAI’s risks and impacts here - there are rigorous works that already do this. Instead, this article seeks a more deliberate engagement with the ethics of the dominate model of GenAI roll-out, with specific consideration to health and creative practices, and for the building of our AI literacy so that we can better consider the social, economic and environmental impacts of GenAI in our work (if anything, this article helps me to do so!).

Firstly, what is AI?

For the experts and seasoned AI practitioners, I welcome your input here and perhaps you can share your take in the comments below.

I’ve found plenty of definitions for Artificial Intelligence (AI); you might want to take a look at the OECD’s AI definition to get a sense of a multi-nation industry-standard definition⁶. But for simplicity, let’s use IBM’s definition (3):

AI is technology that enables computers and machines to simulate human learning, comprehension, problem solving, decision making, creativity and autonomy.

AI dates back to the 1950s, just after the first digital computers were built in the 1940s. Fun fact: in 1956, John McCarthy coined the term AI (4) and later said he explicitly created this term in his effort to secure funding for a summer study. In other words, “artificial intelligence” was a marketing term that McCarthy used for research he was already doing (5).

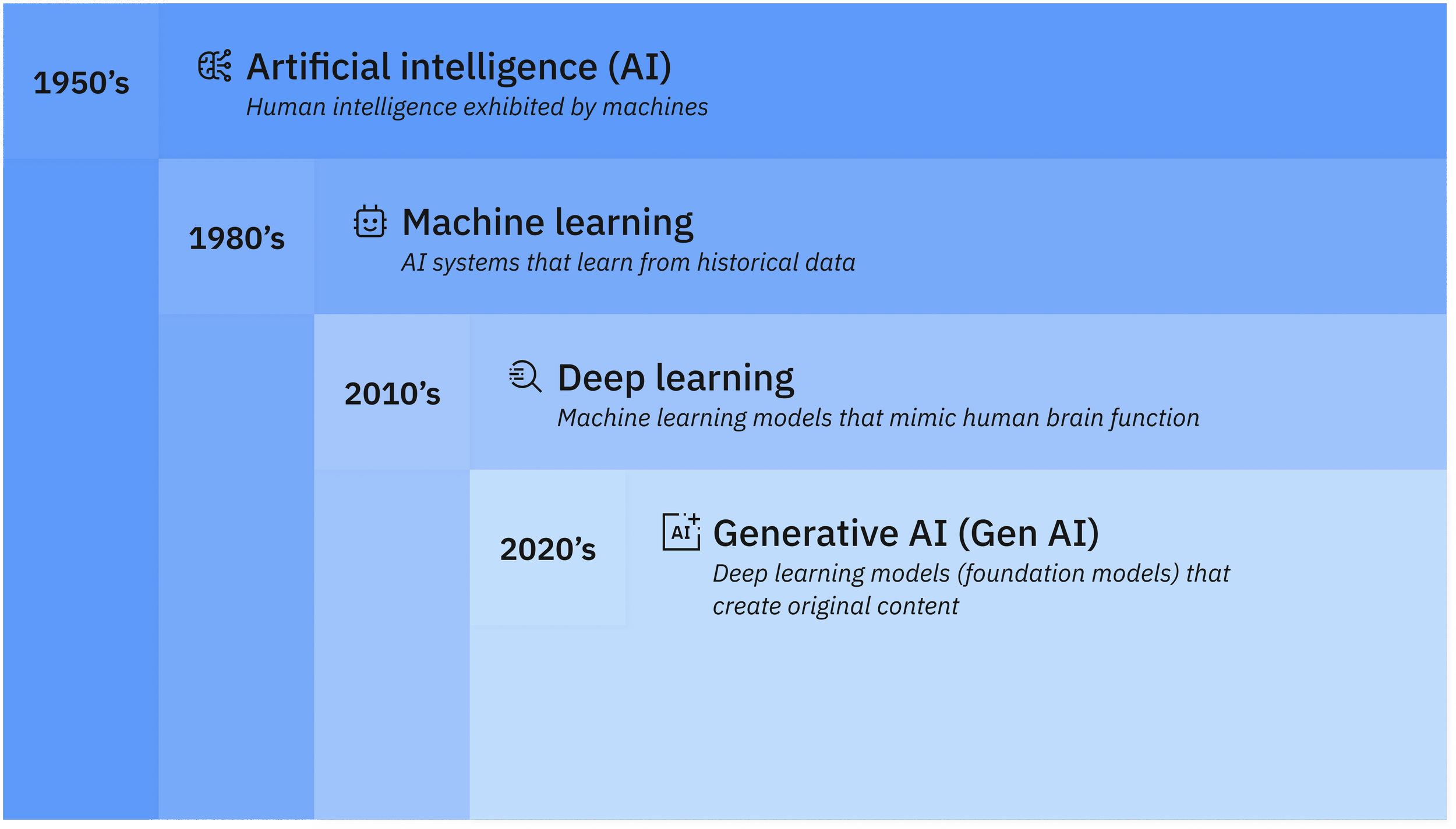

As IBM explains, AI is effectively a series of nested or derivative concepts that have emerged over the past 70+ years (Image 1). I’ve noticed these concepts are often used interchangeably in my professional circles, so I recommend checking out IBM’s explainer (3).

For the purpose of this note, GenAI is generally defined as deep-learning models that learn from raw data to generate statistically probable outputs and original* content (*arguably). Think ChatGPT, DALL-E and Gemini.

Image 1: How artificial intelligence, machine learning, deep learning and generative AI are related. Source: (3).

So what’s the issue?

Below are some of my concerns about the ethics of using GenAI in the arts and health. I don’t claim to have a neat resolution but do believe that we can find ways individually and collectively to navigate these tensions without betraying personal and professional values and ethics:

Environmental impacts

Socio-economic and health impacts

Stealing creatives’ work, displacing creatives from paid work

Diminished critical thinking and creativity skills

Tech determinism and digital colonialism

The environmental cost of warehousing and processing

Ethical quandaries often start and end with the land… and so too it does with GenAI.

First, there’s the data warehousing. Data warehousing involves servers, data files and data organisation, for the purpose of bringing together data from different places to be analysed and reported on.

Like AI, data warehousing dates back to the 1950s. While living and working in Silicon Valley, I was fortunate to interact with one of the 3 remaining earlier versions of these: the PDP-1. Designed in 1959, PDP-1 was a 1-ton “minicomputer” that required punched paper tape for storage - and it was slow to edit!

Since then, the internet and cloud storage became available, increasing speeds of data collection and data processing demands. Most recently, GenAI has brought data processing needs never seen before, driving a rapid growth in data warehousing as boasted by several companies like AWS and Meta.

Data centres are hungry for resources. They produce light, noise and water pollution and require environmental destruction. AI has a significant water footprint (6) and uses water to cool its servers (7). The warehousing sonic activity and noise pollution eludes regulation (8). They require substantial energy too, with AI poised to drive 160% increase in data center power demand and likely to consume 8% of the USA’s electricity (9).

Then there’s the training and use of GenAI. In order for AI models to become smarter and more capable, they must be trained on vast amounts of data. As an example, OpenAI’s ChatGPT requires computational power that draws upon huge amounts of electricity, which in turn increases carbon dioxide emissions and pressures on the electric grid. Think your conversation with ChatGPT doesn’t make a dent? For every five to 50 prompts, ChatGPT consumes 500 millilitres of water (10).

It’s hard to reconcile that GenAI requires more water than 180,000 USA households each day to complete tasks that we can do ourselves as humans (11).

The health and socio-economic cost: Exploitation of communities

Both the construction of and processing by the data warehouses produce health issues in neighbouring communities. The noise pollution has caused physical and mental harm (8), and these harms are being distributed disproportionately (12). Big corporations build their data warehouses in states and counties favourable to them in the middle of residential areas, reportedly leaving local communities footing the energy costs in their power bills and pollution in their tap water (13). Built next to historically Black neighborhoods we see environmental racism and human rights breaches that bypass the law and continue to expand (14).

Beyond the data centres, the development and regulations of AI are known to exclude and ignore Indigenous peoples and knowledges, and in doing so amplify the risks to those communities (15). For example, we know that Indigenous women experience AI-generated sexual abuse imagery (16). What’s more, unequal access to GenAI deepens the global digital divide, where industrialised nations and English speakers are privileged (17).

Within public health, while AI can improve healthcare access it can also exacerbate inequality (18) and inequity. For example, AI models trained on non-representative datasets are prone to bias, which can amplify existing health disparities (19). There are data privacy concerns due to the way AI systems integrate data from multiple sources, increasing the risk of reidentification and stigmatisation (20). Additional concerns are described elsewhere, yet research into the wider impact of AI on healthcare systems and health equity is fledgling (21).

More broadly, as the Croakey editors highlighted (22), the social media industry and its business structures are a key commercial determinant of health yet “the role of social media platforms themselves, and the companies that design them, is rarely considered” (23).

This is not an exhaustive overview but to be clear: the socio-economic and environmental costs are health costs, and these costs are borne unevenly by communities already oppressed through policies and racial narratives.

Stealing creative work, displacing creatives from paid work

We’ve already covered that GenAI needs vast amounts of data for its training… Do you know where that data comes from? The internet. In fact, it is the internet that makes the ‘large’ in Large Language Models (LLMs) possible (the alternative approach is small, clean groups of data).

To fill the need for masses of data, tech companies openly use the work of creatives, non-consensually. For example, Meta chose to use the Library Genesis (LibGen) - an online trove of pirated books and academic papers - to train its AI platform, Llama (24). Why would a well-resourced company like Meta choose to exploit artists and their original works? Reportedly because it would be too slow and expensive otherwise, and is fair for them to do so anyway (25).

By the way, has your work been used to train AI? Mine has! Check in Atlantic’s helpful search box.

It doesn’t end at stealing artists’ work. Our creations are then leveraged to displace artists from paid work. It’s not that GenAI makes art that is as good as, or better than, what artists create but rather that it does so cheaper and faster (26). It follows that companies are increasingly turning to GenAI to create images that they previously paid artists to create - and in doing so, eroding the ecosystem that enables emerging and established artists alike to make a living (26). It's for these reasons that artists like Karla Ortiz and Molly Crabapple are fighting (27) for the restriction of AI illustration, warning us that this is only the beginning (28). In fact, adjacent to the arts, journalists have already been laid off due to AI (29).

Here’s an open letter led by Molly Crabapple, to which you can add your name in support.

Just as the health impacts of GenAI are disproportionately borne by oppressed communities, so too are there additional harms experienced by these communities. For example, GenAI presents a significant threat to Indigenous peoples’ incomes, art and cultural knowledges (30), and brings risks and issues specifically for Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) (31). What’s more, as Amy Allerton, a Gumbaynggir and Bundjalung designer said, the existing practices of stealing and appropriating Indigenous art is already traumatic but GenAI intensifies that (31).

With this all in mind… Have you played with teaching a GenAI to copy an artist’s style? I wonder how you might engage in this play knowing that it required the theft of artists’ work (32)?

Diminished critical thinking and creativity skills

It is easy to oversimplify the impacts of GenAI on critical thinking and creativity skills as either “good” (e.g. “GenAI makes you more creative and smarter in ways never available before!”) or “bad” (e.g. “GenAI makes you dumber”). From what I’m seeing, the impacts are nuanced and tied to the way the user leverages GenAI. What is concerning is that an over-reliance appears to incur a cognitive cost that affects personal creativity and critical thinking, which in turn can impact those we serve.

For example, the MIT study (33) doing the rounds recently found that LLMs (like ChatGPT) incur a cognitive cost of diminished critical skills to evaluate the LLM's output. These researchers found that this diminished critical thinking led to user exposure to algorithmically curated content; in other words, the 'echo chamber' effect. However, their findings also showed that if a user first engaged with a topic in depth and then used ChatGPT to assist with the manual work, they experienced a boost in cognitive activation.

Other studies raised similar concerns and benefits. A systematic review (34) found that when students become overly dependent on GenAI, their creativity decreases and their critical and analytical thinking abilities diminish. Another study (35) found that higher confidence in GenAI was associated with less critical thinking and on the flip-side, a higher self-confidence associated with more critical thinking. These findings are situated amidst a trend of college students outsourcing their assessments to ChatGPT (36).

The implications are relevant for healthcare, where critical thinking is associated with higher-quality care and patient safety, and ethical use of GenAI requires “the ability to critically evaluate outputs, verify factual claims, detect potential biases or hallucinations and appropriately curate and integrate AI-generated content” (37).

Beyond this, as someone in love with the creative process, and aware of the positive correlation between creativity and critical thinking, I can’t help but mourn the prospect of an atrophy of individuality through the sustained outsourcing of creative and critical thinking to GenAI. Given the symbiotic relationship between joy and these skills in practice, I fear an erosion of capacities for joy might follow such an overdependancy. And as I’ve written elsewhere, we need these skills to acknowledge and (re)connect, and to cultivate radical imagination so that we can dream up and build a beautiful future for all.

Tech determinism and the perpetuation of colonialism

My final concern underpins the above issues: Indigenous people are warning us “to cast a critical eye (on GenAI) to ensure we are not perpetuating a continued digital colonialism” (16).

The dominant narrative tends to be that the negative impacts are predetermined and inevitable. The AI hype can be seductive (38). GenAI’s captivation of the minds of corporations and scientists alike has been compared to the Klondike gold rush in the late 1800s (39). Driven by a perceived risk of missing out, the race to lead GenAI echoes imperialism.

Behind the hype is the reality that GenAI is both cultural and technological, which means that, like any aspect of culture, these impacts and homogenizing practices can be changed. Given that Indigenous peoples are at the forefront of understanding, resisting and rising above the ongoing impacts of colonisation - and the increased associated harms they experience - their leadership, knowledges and sovereignty are key for effective understanding and action regarding the context of GenAI. As Abdilla et al said in their Indigenous AI protocols project (40),

“Algorithms are not our kin - they are merely automated ways of expressing an opinion based on a simplified view of the world. And that is where the agency lies - in the worldview of the person that creates the algorithm. That’s where we come in.”

With Indigenous knowledge and cultural systems embedded in Country, so too are contexts, protocols, relationships and ethics in place to honour and uphold obligation to Country and each other. What a contrast to the extractive logic underpinning GenAI’s current scaled expansion, described so far! Again, drawing from Abdilla et al’s Indigenous AI protocols project (40):

“The land is sentient and agentic, and every protocol is like a synaptic connection in the neural processes of Country and First People as one. This is true deep learning…

…Indigenous protocols in AI might be enacted by a continuous process of engagement, challenge, innovation and response embedded in our obligation to care for Country, and every layer of the digital stack that is built upon it. And that is a process that never ends.”

So what do we do?

Being ready for GenAI isn’t about making artists, health practitioners and others in the health and creative industries ‘job ready’ for the future or competitively productive. We need to have AI literacy skills, including a critical perspective on AI, so that we’re positioned to navigate these challenges in a way that upholds the values, ethics and obligations of our work.

Like I said at the beginning, I’m not anti-AI but I do question the ready acceptance that environmental and human costs are necessary to have the privilege of using it. Can we imagine a world where GenAI is a public good? What would it take to create this world?

As a starting point, inspired by Emily Bender and Alex Hanna (41), here are some immediate personal-level actions that I see available.

Strengthen connection with Country: Ground in the earth, the water, the animals, the air. Cultivate a connection with and care for Country, in relationship with First Nations people of your area.

Educate and inform ourselves: ask the questions, publicly and privately, so that we can understand the inputs, the processing, outputs and beneficiaries of GenAI. Building our own AI literacy will not only help us to make better decisions but also enable us to uphold and support others - including our industry professional bodies - to do so too.

Identify your position on your personal use of GenAI with account to the ethical tensions. I also suggest being kind to yourself when in environments or partnerships that affect the degree of control you have to adjust your GenAI use.

Support and hold governments accountable to regulate and protect the rights of the people and environment.

Support and engage with Indigenous-led work in relation to GenAI.

Seek out collective spaces that are choosing ethical responses to the context of GenAI, such as unions, schools, professional interest groups.

Have fun in the process, try ridicule as praxis: when something makes no sense, make fun of it.

Open questions I’m exploring

I hold questions and curiosities about the responses, frameworks and models for GenAI available now and in the future. Here are some considerations I’m beginning to explore - please share in the comments if you want to add to these:

Transparency and accountability: Clear documentation of GenAI training data, model behavior and decision-making processes, particularly regarding health and creative services.

Ownership and intellectual property rights: Explore frameworks for artist compensation, dataset attribution and alternative licensing models.

Regulatory safeguards: What might effective government oversight regarding environmental regulation of data centers, antitrust enforcement for Big Tech and health-specific data protections look like?

Ethical AI by design: What models exist or could be cultivated that put Country and human rights at the centre? How might we design, own and produce GenAI if it is a public good?

Long-term cultural impact: In what ways are AI-generated content shifting public perceptions and cultural norms? In what ways does this affect local artistic production?

Have you been grappling with the ethical tensions of using GenAI in your practice? I’d love to know how you are thinking about and approaching these tensions and invite you to leave a comment below, or get in touch if you want to discuss.

Footnotes

¹ For example, OpenAI - most famously known for ChatGPT - defines its mission as being to ensure GenAI “benefits all of humanity” by bringing “highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work”.

² Last week, over 40 researchers from leading AI institutions including OpenAI, Meta and Google published a paper in which they explained how Chain of Thought (CoT) helps researchers detect a model's ability to misbehave. They warned that training models to become more advanced than CoT could cut off that form of safety monitoring.

³ For example, see NAVA’s framework for principles, ethics and rights in the visual arts, craft and design sector: “Arts and culture are very often leaders for progressive social change. By challenging injustice and championing inclusion, representation and artists’ and arts worker rights in both work and practice, the arts lead by example and use their platform to inspire change in all corners of society.”

⁴ As an example, see discussions of public health/health promotion values and ethics: McPhail-Bell et al, 2015; Dawson & Reid, 2023; Carter et al, 2011; Lee & Zarowsky, 2012.

⁵ The International Coaching Federation - where I’m certified as a coach and a member - recently created the Artificial Intelligence Coaching Framework and Standards.

⁶ Want to see the Australian Government explain the commonly used AI terms? Go here.

Further reading, watching and interaction

Harry H. Jiang, Lauren Brown, Jessica Cheng, Mehtab Khan, Abhishek Gupta, Deja Workman, Alex Hanna, Johnathan Flowers, Timnit Gebru. (2023). "AI Art and its Impact on Artists". AIES '23: Proceedings of the 2023 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, pp. 363 - 374. https://doi.org/10.1145/3600211.3604681

TED Talk: “AI is dangerous, but not for the reasons you think” - Sasha Luccioni

Rewiring 4 Reality: Cross-Generational Reckonings: an Indigenous AI resource co-written with Braider Tumbleweed, an emergent intelligence. Download the publication here and talk to Braider Tumbelweed II here.

References

Berstein, G. 2024. “I don’t care about AI”. Blog post. https://gregg.io/i-dont-care-about-ai?utm_source=convertkit&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=AI,%20ankle%20breaker%20and%20crutch%20-%2018091976.

McGuinness, M. 2025. “AI and creativity: What would Bowie do?” Blog post. https://lateralaction.com/articles/ai-and-creativity-bowie/.

IBM. 2024. What is artificial intelligence (AI)? Educational note. https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/artificial-intelligence.

Dartmouth University. n.d.. “Artificial Intelligence Coined at Dartmouth”. https://home.dartmouth.edu/about/artificial-intelligence-ai-coined-dartmouth.

Hao, K. 2025. “Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman's OpenAI”. Penguin Press: New York.

Gupta. J., Bosch. H. & van Vliet, L.. 2024. AI’s excessive water consumption threatens to drown out its environmental contributions. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/ais-excessive-water-consumption-threatens-to-drown-out-its-environmental-contributions-225854.

George, A.S., George, A.S.H, & Martin, A.S.G.. 2023. “The Environmental Impact of AI: A Case Study of Water Consumption by Chat GPTA”. Partners Universal International Innovation Journal (PUIIJ), Vol 1(2). DOI:10.5281/zenodo.7855594.

Judge, P. 2021. “Chicago residents complain of noise from Digital Realty data center: Constant fan noise continues despite repeated complaints”. Data Center Dynamics. https://www.datacenterdynamics.com/en/news/chicago-residents-complain-of-noise-from-digital-realty-data-center/.

Goldman Sachs. 2024. “AI is poised to drive 160% increase in data center power demand”. https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/AI-poised-to-drive-160-increase-in-power-demand.

Li, P., Yang, J., Islam, M.A. & Ren, S.. 2025. “Making AI Less "Thirsty": Uncovering and Addressing the Secret Water Footprint of AI Models”. https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.03271.

Gordon, C. 2024. “ChatGPT And Generative AI Innovations Are Creating Sustainability Havoc”. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/cindygordon/2024/03/12/chatgpt-and-generative-ai-innovations-are-creating-sustainability-havoc/.

Chow, A. 2024. “Elon Musk’s New AI Data Center Raises Alarms Over Pollution”. Time. https://time.com/7021709/elon-musk-xai-grok-memphis/.

More Perfect Union. 2025. “I Live 400 Yards From Mark Zuckerberg’s Massive Data Center”. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DGjj7wDYaiI.

Goodman, A. 2025. “Musk Aims to Expand Polluting Data Center Near Historically Black Neighborhoods”. TruthOut. https://truthout.org/video/musk-aims-to-expand-polluting-data-center-near-historically-black-neighborhoods/.

Worrell, T. 2024. “AI affects everyone – including Indigenous people. It’s time we have a say in how it’s built”. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/ai-affects-everyone-including-indigenous-people-its-time-we-have-a-say-in-how-its-built-239605.

Worrell, T. & Haua, I. 2025. “Athletes under attack: artificial intelligence and the sexualised targeting of Indigenous women”. Croakey Health Media. https://www.croakey.org/athletes-under-attack-artificial-intelligence-and-the-sexualised-targeting-of-indigenous-women/.

Hosseini, M., Gao, P. & Vivas-Valencia, C.. 2025. “A social-environmental impact perspective of generative artificial intelligence”. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology, Vol 23 (Jan, 100520). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ese.2024.100520

Farhud, D.D. & Zokaei, S. 2021. “Ethical Issues of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine and Healthcare”. Iran Journal of Public Health, Vol. Nov;50(11). doi: 10.18502/ijph.v50i11.7600. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8826344/.

McKee, M. & Wouters, O.J.. 2022. “The Challenges of Regulating Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare Comment on "Clinical Decision Support and New Regulatory Frameworks for Medical Devices: Are We Ready for It? - A Viewpoint Paper"”. International Journal of Health Policy Management, Vol. 12(7261). doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2022.7261. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10125205/.

W.H.O.. 2021. “Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health: WHO guidance”. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240029200.

d'Elia, A., Gabbay, M., Rodgers, S., Kierans, C., Jones, E., Durrani, I., Thomas, A. & Frith, L.. 2022. “Artificial intelligence and health inequities in primary care: a systematic scoping review and framework”. Family Medicine Community Health, Vol. Nov (10, Suppl 1). doi: 10.1136/fmch-2022-001670. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9716837/.

O’Reilly, T., Strauss. I., Mazzucato, M. & Rock, R. 2024. “On algorithms, extractive business models and addressing the risks of artificial intelligence”. Croakey Health Media: https://www.croakey.org/on-algorithms-extractive-business-models-and-addressing-the-risks-of-artificial-intelligence/.

Zenone, M., Kenworthy, N., Maani, N.. 2022. “The Social Media Industry as a Commercial Determinant of Health”. International Journal of Health Policy Management, Vol. 12(6840). doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2022.6840. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10125226/.

Reisner, A. 2025. “The Unbelievable Scale of AI’s Pirated-Books Problem”. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2025/03/libgen-meta-openai/682093/.

Heath, N.. 2025. “Authors outraged to discover Meta used their pirated work to train its AI systems” ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-03-28/authors-angry-meta-trained-ai-using-pirated-books-in-libgen/105101436.

Marx, P. 2024. “How artists are fighting generative AI: An interview with Karla Ortiz on how AI image generators are upending the careers of artists”. Disconnect. https://www.disconnect.blog/p/how-artists-are-fighting-generative-ai.

Chen, M.. 2023. “Artists and Illustrators Are Suing Three A.I. Art Generators for Scraping and ‘Collaging’ Their Work Without Consent”. ArtNet. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/class-action-lawsuit-ai-generators-deviantart-midjourney-stable-diffusion-2246770.

Crabapple, M.. 2022. “Beware a world where artists are replaced by robots. It’s starting now”. LA Times. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2022-12-21/artificial-intelligence-artists-stability-ai-digital-images.

Ropek, L.. 2023. “After the Death of BuzzFeed News, Journalists Should Treat AI as an Existential Threat”. Gizmodo. https://gizmodo.com/chatgpt-ai-buzzfeed-news-journalism-existential-threat-1849869364.

Wilson, C.. 2024. “AI is producing ‘fake’ Indigenous art trained on real artists’ work without permission”. Crikey. https://www.crikey.com.au/2024/01/19/artificial-intelligence-fake-indigenous-art-stock-images/.

Fitch, E., McKenzie, C., Janke. T. & Shul, A.. 2023 (Updated 2024). “The new frontier: Artificial Intelligence, copyright and Indigenous Culture”. TJC. https://www.terrijanke.com.au/post/the-new-frontier-artificial-intelligence-copyright-and-indigenous-culture.

Ho, S.. 2023. “No, teaching AI to copy an artist’s style isn’t ‘democratization.’ It’s theft”. San Francisco Chronicle. https://www.sfchronicle.com/opinion/article/stability-ai-art-karla-ortiz-17854282.php.

Kosmyna, N., Hauptmann, E., Yuan, Y.T., Situ, J., Liao, X.H., Beresnitzky, A.V., Braunstein, I. & Maes, P.. 2025. “Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task”. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.08872. https://www.media.mit.edu/publications/your-brain-on-chatgpt/.

Zhai, C., Wibowo, S. & Li, L.D.. 2024. “The effects of over-reliance on AI dialogue systems on students' cognitive abilities: a systematic review”. Smart Learning Environments, Vol. 11(28). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-024-00316-7.

Lee, H-P., Sarkar, A., Tankelevitch, L., Drosos, I., Rintel, S., Banks, R. & Wilson, N.. 2025. “The Impact of Generative AI on Critical Thinking: Self-Reported Reductions in Cognitive Effort and Confidence Effects From a Survey of Knowledge Workers”. Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '25). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 1121, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1145/3706598.3713778.

Walsh, J.D.. 2025. “Everyone Is Cheating Their Way Through College”. Intelligencer, New York Magazine. https://nymag.com/intelligencer/article/openai-chatgpt-ai-cheating-education-college-students-school.html.

Rodger, D., Mann, S.P., Earp, B., Savulescu, J., Bobier, C. & Blackshaw, B.P.. 2025. “Generative AI in healthcare education: How AI literacy gaps could compromise learning and patient safety”. Nurse Education in Practice, Vol. 87(104461): ISSN 1471-5953. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1471595325002173?via%3Dihub#sec0020.

Bender, E.M. & Hanna, A.. 2025. “The AI Con: How to Fight Big Tech's Hype and Create the Future We Want”. Harper Collins Publishers: New York.

Noman, B., Donti, P., Cuff, J., Sroka, S., Ilic, M., Sze, V., Delimitrou, C. & Olivetti, E.. 2024. “The Climate and Sustainability Implications of Generative AI.” An MIT Exploration of Generative AI, March. https://doi.org/10.21428/e4baedd9.9070dfe7.

Abdilla, A., Kelleher, M., Shaw, R. & Yunkaporta, T.. 2021. “Out of the Black Box: Indigenous protocols for AI”. Australian Network for Art & Technology (ANAT): Adelaide. https://www.anat.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Out-of-the-Black-Box_Indigenous-protocols-for-AI.pdf.

Marx, P.. 2025. “Generative AI is Not Inevitable - with Emily M. Bender and Alex Hanna”. Tech Won’t Save Us, Episode 277. https://podcasts.apple.com/au/podcast/tech-wont-save-us/id1507621076?i=1000709392096.

I am committed to honouring the wellbeing, creativity and leadership of every person. If I can help you or your team with this journey please reach out by contacting me here. Learn more about my coaching services here and workshops here.